Imagine a story’s structure as a war and the Main Character as a soldier making his way across the field of battle. In your mind’s eye, you likely see they whole scene spread out in front of you, as if you were a general on a hill watching the conflict unfold.

That all-seeing “God’s eye view” is a perspective not available to the Main Character, but only the author and audience (as he chooses to reveal it, here and there, casting light on that dark understanding of what is really going on or keeping the readers in the dark.

But there is a second point of view implied in this war of words – that of the Main Character himself. The Main Character has no idea what lies over the next hill, or what troubles may be lurking in the bushes. Like all of us, he must rely on our experience in trying to make it through alive.

The view through the eyes of the Main Character puts your readers in his shoes, experiencing the pressures first hand, feeling the power of the moment. In a sense, this most perspective connects the Main Character’s tribulations (both logistic and emotional) to those we all grapple with in real life. It draws us in, makes us personally involved, and also causes us to see the message or moral of the story as being applicable to our own journey.

Many authors establish both the overall story and the Main Character’s glimpse of it and stop there, believing they have covered all the angles. After all, the Main Character can’t see the big picture and that overview can’t portray the immediacy of the struggle on the ground. All bases covered, right?

In fact, no. Suddenly, through the smoke of dramatic explosions the Main Character spies a murky figure standing right in his path. In this fog of war, he cannot tell if this other soldier is a friend or foe. Either way, he is blocking the road.

As the Main Character approaches, this other soldier starts waving his arms and shouts, “Change course – get off this road!” Convinced he is on the best path, the Main Character yells back, “Get out of my way!” Again the figure shouts, “Change course!” Again the Main Character replies, “Let me pass!”

The Main Character has no way of knowing if his opposite is a comrade trying to prevent him from walking into a mine field or an enemy fifth column combatant trying to lure him into an ambush. But if he stops on the road, he remains exposed with danger all around. And so, he continues on, following the plan that still seems best to him.

Eventually, the two soldiers converge, and when they do it becomes a moment of truth in which one will win out. Either the Main Character will alter course or his steadfastness will cause the other soldier to step aside.

This other soldier is called the Influence character, and though you may not have heard of him, this other soldier is essential to describing the pressures that bring the Main Character to a point of decision.

In our own minds we are often confronted by issues that question our approach, attitude, or the value of our hard-gained experience. But we don’t simply adopt a new point of view when our old methods have served us so well for so long. Rather, we consider how things might go if we adopted this new system of thinking right up to the moment we have to make a choice.

It is a long hard thing within us to reach a point of change, and so too is it a difficult feat for the Main Character. In fact, it takes the whole story to reach that point of climax where the Main Character must choose to stay on course or to step off into the darkness, hoping they’ve made the right choice – the classic “Leap of Faith.”

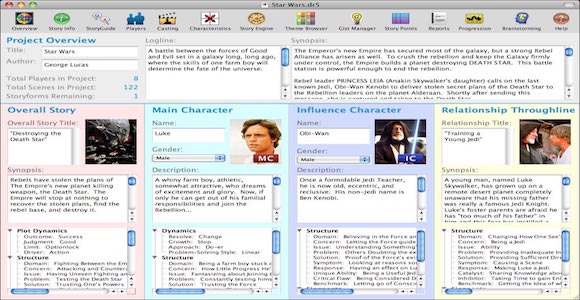

This other character provides a third perspective to a story’s structure – that of an opposing belief system that the Main Character is pressured to consider. What would the original Star Wars have been without Obi Wan Kenobi continually urging Luke to “Trust the force?” How about A Christmas Carol without Marley’s ghost, as well as the ghosts of Past, Present, and Future?

Without an Influence character, there is no reason for the Main Character to question his beliefs. But just having an opposing perspective isn’t all that an Influence Character brings to a story.

A convincing theme or message is not built just by establishing an alternative world view to that of the Main Character. That would come off as simply moralizing since it presents the two sides as cut and dried, in black and white. Few life-changing decisions in life are as simple as that.

Rather, the two views must also be played against each other in many scenarios so the Main Character (who represents us all) can begin to connect the dots and ultimately choose the tried and true approach that isn’t working or the new approach that has never been tried. In other words, at the moment of conflict, both courses are evenly balanced which is why, no matter which side the Main Character comes down on, it is a leap of faith.

It is that repeated questioning of the Main Character’s closely held beliefs that comprises the fourth perspective of our story when seen as a war – the personal story between the Main Character and the Influence Character in which the author’s message is argued.

This fourth point of view elevates a structure from being a simple tale that states “here is how it is,” to a fully developed story that makes the case for “here’s why it is as it is.” Such stories feel far more complete, even though they may still work well-enough to be successful without it.

For example, in the movie, A Nightmare Before Christmas, Jack Skellington, King of Halloween Town, is dissatisfied with his lot in life and decides to take over Christmas by kidnapping Santa Claus.

The kidnapping and all that follows in the plot is that Overall perspective of the general on the hill.

Jack is the Main Character, trying to improve his life through altering his situation, embodying perspective number two.

Jack’s girlfriend, Sally, is the Influence Character, providing the third perspective: an alternative belief system. As Wikipedia puts it: “Sally is the only one to have doubts about Jack’s Christmas plan.” Essentially, he tell Jack that Halloween and Christmas should not be mixed and he should be satisfied with who he is.

But that fourth perspective is missing – the thematic argument between those two conflicting points of view that would have provided a strong and organic message to the story. Sally states her opposition, but she and Jack never pit one way of looking at the world against the other, not through discussions, nor argument, nor even through a series of scenes illustrating the value of one over the other.

Think back to A Christmas Carol. How many times is Scrooge’s world view contrasted against that of the ghosts in a whole series of scenarios? But in Nightmare, the opposing world view is stated but never argued, leaving the story, though incredibly inventive and exciting, somehow less satisfying in a way the audience can’t quite identify.

All four of these perspectives are needed for a story structure to be as powerful as it can be. In developing your own stories, consider our analogy of story structure as war to ensure that each of them is present, and your story will be far stronger for it.

This article is drawn from concepts in our

Dramatica Story Structure Software

#1 – Building Size (Changing Scope)

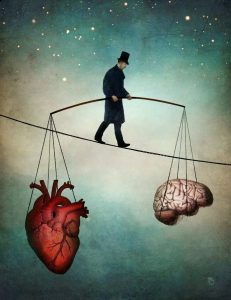

#1 – Building Size (Changing Scope) Realize that your mind is a narrative-generating machine. That is why narratives exist in the first place: because they mirror the processes of the mind. But the mind is also a repository of topical information – subject matter – and engages in the process of synthesizing two or more old ideas into a new one. The new ideas may or may not fit into the narrative the mind is constructing. And yet the heart is drawn more to the new ideas, just as the mind is drawn more to a balanced and complete structure.

Realize that your mind is a narrative-generating machine. That is why narratives exist in the first place: because they mirror the processes of the mind. But the mind is also a repository of topical information – subject matter – and engages in the process of synthesizing two or more old ideas into a new one. The new ideas may or may not fit into the narrative the mind is constructing. And yet the heart is drawn more to the new ideas, just as the mind is drawn more to a balanced and complete structure.

You must be logged in to post a comment.