As writers, we all know that characters need drive or their actions will come across as unmotivated. But what is drive, and where does it come from?

At a minimum, every character needs a reason to explain the choices they make or to do the things they do. For example, the ex-con who has made a new life going straight takes on one more job because his daughter needs a surgery he can’t afford. Or, a mother of three who is belittled and abused by her husband falls deeply in love with a man she met in a chance encounter but can’t bring herself to run away with him because she was abandoned by her own mother as a child.

These motivations are enough to satisfy the basic need to understand what drives each character, yet the reasons given still seem unrealistically simple, superficial, or just too pat.

So how do you design drives for your characters that ring true to the complex web of conflicting feelings that form the motive forces each of us grapple with in everyday life? For that, you need to dig down beneath the reasons a character responds and acts as they do in order to discover their justifications.

Justifications are the tangled up knots of experience that determine both our emotional responses to life situations as well as the courses of actions we think are best. Like a ball of snarled rubber bands, justification creates a lot of potential, and if something starts to cut into it, sometimes it slowly unravels, and other times it snaps explosively.

The creation of Justification in characters is the purpose of and reason for Backstory. The dismantling of Justification is the purpose and function of the story itself. The gathering of information necessary to dismantle Justification is the purpose and function of the Scenes, with every Act completing a major new epiphany. It is the nature of the specific Justifications explored in a particular story that determines the story’s message.

Understanding justification is essential to understanding the dynamics that drive story structure. Fortunately this is not as hard as it might sound as we do this intuitively every day. We all justify, for better or worse, and then subconsciously add the results of our latest use of the process into our experience base, slightly changing our view of the world every time we do it.

So my purpose here is not to tell you something you don’t already know, but to elevate that process from automatic to intentional. In this way, you can more accurately and powerfully sculpt your characters, what drives them, and how that leads to the behaviors they exhibit.

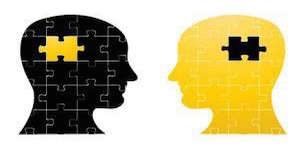

Technically speaking, Justification is a state of mind wherein the Subjective view differs from the Objective view. Okay, fine. But how about in plain English!!!! Very well… When someone sees things differently than they are, they are Justifying. This can happen either because the mind draws a wrong conclusion or assumes, or because things have actually changed in a way that is no longer consistent with a held view.

All of this comes down to cause and effect. For example, suppose you have a family with a husband, wife and young son. Here is a sample backstory of how a particular little boy might develop a particular justification that could plague him in later life….

The husband works at a produce stand. Every Friday he gets paid. Also every Friday a new shipment of fresh beets comes in. So, every Friday night, he comes home with the beets and the paycheck. The paycheck is never quite enough to cover the bills and this is weighing heavily on his wife. Still, she knows her husband works hard, so she tries to keep her feelings to herself and devotes her attention to cooking the beets for her husband and her son.

Nevertheless, she cannot hold out forever, and every Friday evening at some point while they eat, she and her husband get in an argument. Of course, like most people who are trying to hold back the REAL cause of her feelings, she picks on other issues, so the arguments are all different. Their son, therefore, cannot see an immediate cause for the problem so he desperately looks for one so he can anticipate the problem and either avoid it or at least be prepared – something we all do called “problem-solving.”

Now the child might come to feel that Friday nights are gonna be bad or that dinner is a horrible time, but in our story, he casts his eyes down at his plate of beets so as to shut out the arguing, and this becomes the common factor he fixates on as his canary in the mine – a harbinger of a fight to come. And, of course, all of this is going on in his heart subconsciously, below the level of his conscious awareness.

With this backstory, we have laid out a series of cause and effect relationships that lead to the child establishing a justification – a connection between the way his parents fighting makes him feel and the serving of beets. With this potential we have wound up the spring of the dramatic mechanism for our story, and now we are ready to begin the fore story to see how that tension creates problems.

The Story Begins: The young boy, now a grown adult with a wife and child of his own, sits down to dinner with his family. He begins to get belligerent and antagonistic. His wife does not know why he is suddenly acting this way or what she may have inadvertently done to trigger his behavior. In fact, later, he himself cannot say why he was so upset. But we, the readers or audience, know it is because his wife served beets.

Looking toward the backstory, it is easy to see that from the young boy’s knowledge of the situation when he was a child, the common element that he fixated on whenever his parents argued was the serving of beets. They never argued about the money directly, and that would probably have been beyond his ken anyway. And so, he established a subconscious correlation- a justification – that associated angry interchanges with the presence of beets. And if there is no argument, he starts one, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Certainly, this makes no sense to the conscious mind – one would never accept nor act upon such a ridiculous association. But the subconscious does not reason, it just associates. And therefore, connections made in such a way are simply accepted as being truisms.

Obviously, it is not stupidity that leads to such misconceptions, but lack of accurate information. The problem is, we have no way of knowing if we have the proper information or not, for we can never determine how much we do not know or what we may have unintentionally misconstrued. Justification is nothing more than a human trait by which we see a repetitive proximity between two items or between an item and a process and assume a causal relationship, as in “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” or “one bad apple spoils the bunch.”

But why is this so important to writing stories? In fact, the purpose of stories is to shine a light on these erroneous connections that can get stuck in our motivations, just as Scrooge is shown that his world view is in error by having the ghosts expose the roots of his justifications and their ramifications on others. Stories show us a greater Objective truth that is beyond our limited Subjective view. They exist to convince us that if we feel something is a certain way, even based on extensive experience, it is possible that it really is not that way at all, at least in this particular kind of situation. And the more we consume stories, as readers or audience members, the more skillful we become at questioning our most strongly held assumptions and beliefs, leading to a more clear understanding of our lives, and therefore to a better ability to navigate them.

But not all assumptions of cause and effect are wrong. In fact, most of the time we get it right, seeing repeated connections over and over again and accurately accepting that there is a direct connection between one set of circumstances and what happens next.

Characters, whether their assumptions are right or wrong, will be tested by a new set of circumstances that make it appear as if a given earlier assumption is actually wrong. But are they truly wrong or do they just appear to be wrong? That is the dilemma that leads to a character facing a leap of faith – to stick with the tried and true that currently seems to be failing, or to embrace a new understanding that seems to explain more but has never been tried.

The question here is that in our lives, our understanding is not only limited by past misconceptions, but by lack of accurate information about the present as well. And stories are all about sending a message that in this particular kind of scenario, trust your beliefs OR in this particular scenario, abandon your beliefs.

“Keeping the faith” describes the feeling that drives characters who refuse to change their long-held views., even in the face of major contradiction, holding on to one’s views and dismissing the apparent reality as an illusion or falsehood.

“Seeing the light” describes the feeling that drives characters who ultimately embrace a new view, even in the face of potential disaster, accepting a new reality and recasting the previous belief as either having always been in error, or at least not being accurate right now.

At the climax of a story, the need to make a decision between remaining steadfast in one’s faith or altering it is presented to every main character. Each must make that choice. And as a result of that choice, the character will succeed or fail.

If we decide with the best available evidence and trust our feelings we will succeed, right? Not necessarily. Success or failure is just the author’s way of saying she agrees or disagrees with the choice the character made. So, just making a leap of faith does not, in and of itself, guarantee success. Rather, a story leads a character to a point at which that choice – to change or remain steadfast in one’s beliefs – can no longer be put off. Circumstances are such that failing to make the choice at all leads to certain disaster. The only way to have a chance to succeed is to choose to either stay the course, or to set off in a new direction.

In the original Star Wars movie, for example, Luke Skywalker is ultimately faced with trusting in the targeting computer or in himself and turning off the computer to rely on his own skills in destroying the Death Star. He turns off the computer, trusting in himself, and destroys the Death Star. But that is only one of four possible outcomes.

Imagine if Luke had made the the choice to turn off his targeting computer (trusting in the force), dropped his bombs, and missed the target, Darth blows him up and the Death Star obliterates the rebels… how would we feel? Sure you could write it that way, but would you want to? Perhaps! If you made Star Wars as a government sponsored entertainment in a fascist regime, that might very WELL be the way you would “want” to end it!

But there are still two other options. Suppose Luke left the targeting computer on and succeeded, or if he turned it off and failed. Any of these outcomes makes sense, but each sends different kind of message. And that, as was said in the beginning, is the purpose of stories – to convey a message that a particular believe is a good or bad one to maintain in the given situation that this particular story explores. And you can do that by showing the steadfast choice succeeds or fails, or that change leads to success or failure, each creating a different kind of message.

In summary then, the point of stories is to provide a message about the best way to respond to a specific given problem – either to stick with one’s long-held beliefs or to adopt a new way of looking at things. Backstory explains how a belief was formed through the process of justification. Over the course of the story, circumstances continually build pressure on your main character to change that belief, eventually arriving at a climax that forces a choice because failure is certain if one does not choose at all between the old belief and the new.

By this point, there is equal evidence supporting the original belief as supporting the new one. And so, the main character must make a leap of faith and choose to stick to remain steadfast in its views or to adopt a new view. Either way could lead to success or failure, depending on the flavor of message you wish to impart.

In conclusion then, think about the process of justification when you consider where your characters’ drives come from, how that creates problems for them in the here and now, and the message you want to send. The more you become familiar with how justification works, the more you can take control of the affect your story will have on your readers or audience, and the more adept you may become in making solid choices in your own life as well.

Author’s note: Most of these concepts come from the Dramatica theory of narrative structure I developed along with my writing partner, Chris Huntley. They became the basis for our Dramatica Story Structuring Software. Click the link to try it for free.

Here’s something else I also made for writers…

Problem solving tries to resolve an issue. But if there is an obstacle to a solution, the process of justification tries to find a way around. Sometimes characters get so wrapped up in the attempt to side-step an obstacle that they miss an alternative direct solution.

Problem solving tries to resolve an issue. But if there is an obstacle to a solution, the process of justification tries to find a way around. Sometimes characters get so wrapped up in the attempt to side-step an obstacle that they miss an alternative direct solution.

Check out our new audio program:

Check out our new audio program:

Introduction to StoryWeaver

Introduction to StoryWeaver

Although it is possible to write without the use of characters, it is not easy. Characters represent our drives, our essential human qualities. So a story without characters would be a story that did not describe or explore anything that might be considered a motivation. For most writers, such a story would not provide the opportunity to completely fulfill their own motivations for writing.

Although it is possible to write without the use of characters, it is not easy. Characters represent our drives, our essential human qualities. So a story without characters would be a story that did not describe or explore anything that might be considered a motivation. For most writers, such a story would not provide the opportunity to completely fulfill their own motivations for writing.

There is one special character who represents the argument for an alternative point of view to that of the Main Character. This character, who spends the entire story making the case for change, is called the Influence Character for he acts as an influence to change the direction the Main Character would go if left to his own devices.

There is one special character who represents the argument for an alternative point of view to that of the Main Character. This character, who spends the entire story making the case for change, is called the Influence Character for he acts as an influence to change the direction the Main Character would go if left to his own devices. There’s only one main character in a story. Why? Because a story is about the group experience of trying to achieve a goal. When people come together around a common issue in the real world, they quickly self-organize so that one becomes the Voice of Reason and another the Resident Skeptic, for example.

There’s only one main character in a story. Why? Because a story is about the group experience of trying to achieve a goal. When people come together around a common issue in the real world, they quickly self-organize so that one becomes the Voice of Reason and another the Resident Skeptic, for example.

You must be logged in to post a comment.