At the core of a story’s message is a very simple issue – whether the author is telling us it is better to be like the main character or not. This is usually thought of as the moral of the story and is proven to the readers or audience by how the main character fares after making a choice or taking a leap of faith at the climax.

For characters like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, the message is that it is better to change one’s attitude toward others and adopt a new way of thinking. If you do, things will work out better. But for other characters, such as in Field of Dreams or Rocky, the message is to stick by your beliefs because that’s the only way to solve your problems.

Sometimes change is good, as with Scrooge. But imagine if Ray had given up on building the ball field or Rocky Balboa had determined there was no way to win and he shouldn’t continue to try.

Stories can be written about characters who change or about characters who don’t. That’s the first part of the message. The second part is what happens to the character in the end as a result of their choice to change or not.

This results in four possibilities:

- The main character changes and things work out for the better.

- The main character changes and things work out for the worse.

- The main character remains steadfast and things work out for the better.

- The main character remains steadfast and things work out for the worse.

Each of the four combinations provides a different kind of message about changing or sticking to your beliefs. So far, so good. But now you need to get that message across to your readers or audience.

The first part of conveying your message is to be clear about the nature of the human quality or thought pattern that your moral is about. That aspect of your main character that defines him, just as Scrooge’s lack of concern for his fellow man is the issue at the heart of him. How you do this can be subtle or straight out, but by the time the moment of choice is upon your main character, your audience or reader needs to absolutely and with total clarity know what that issue is or your message will be unclear.

The second part of conveying your message is to show that as a result of his or her choice, your main character is better off or worse off than they were. This element of your message has two components:

- Did they achieve the goal?

- Are they in an emotionally better place than they were.

For example, suppose you have a story in which a character changes his beliefs, achieves the goal, and is elated. That’s fine, and the message is that whatever his issue was, it was good he changed his point of view. But change is not always good, so in another story a character might change his beliefs, still achieve the goal, but be miserable in the end because he hadn’t resolved his anguish or he had to take on an emotional burden to accomplish his quest. For example, in Avengers: Infinity War, the villain Thanos has to kill the person he loves the most to accomplish his goal, and this leaves him logistically satisfied yet emotionally devastated.

On the opposite side, a character might remain steadfast in his beliefs, fail in the goal but find personal salvation or true happiness in the end. Or a character might remain steadfast, succeed in the goal but be left personally raw. An example of this last combination can be seen in Silence of the Lambs in which Clarice Starling is successful in saving the senator’s daughter, but could not let go of the screaming lambs in her memory, as pointed out in the end by Hannibal Lecter (“Tell me, Clarice,” are the lambs still screaming?”) This is why the ending music over her graduation ceremony is so somber – she achieved the goal but could not let go of her angst.

And, of course, you can have the quintessential tragedy in which a change or a steadfast character fails and the goal and is miserable in the end, such as in Hamelt, or the penultimate feel good story in which a change or steadfast character both succeeds in the goal and find (or holds onto) great happiness, true love, etc., as in the original Star Wars movie (Episode IV)

The point here is that change, in and of itself, is neither good nor bad until you see the results of that change. And also, a character does not have to change to grow, but can grow in his or her resolve.

And finally, the ramifications don’t have to be cut and dried: all good or all bad. Rather, by treating the goal and the emotional outcome separately, you have the opportunity to temper your message with bitter sweet and sweet bitter endings as well, thereby creating a more complex message for your readers or viewers.

Also from the author of this article…

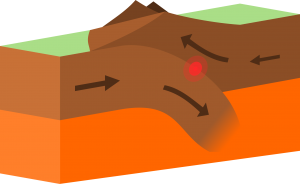

Think of the large structural elements in a story as tectonic plates in geology that push against each other driven by an underlying force. In geology that force is generated by currents in the mantle. In stories, that force is created by the wound-up justifications of the main character that puts him or her in conflict with their world at the point the story begins.

Think of the large structural elements in a story as tectonic plates in geology that push against each other driven by an underlying force. In geology that force is generated by currents in the mantle. In stories, that force is created by the wound-up justifications of the main character that puts him or her in conflict with their world at the point the story begins.

You must be logged in to post a comment.