We think in narrative, but think about topics. Narrative is the operating system of our own minds, and we seek to impose that upon every topic we encounter. For if we can, then we have the most touch-points with our own awareness, and see the most we can of what we are exploring, as well as the forces that operate in that system and hold things together.

That which does not match the schematic of our minds appears to be chaos. But even chaos can be topically related.

The problem for the creative mind is that it wants to have topic and narrative come together in a perfect fit. It is like putting a pencil on a table, and balancing a ruler across it. Topic is on one side and narrative is on the other. If you push the topic side down to the table, like a seesaw, the narrative side will go up, and vice versa.

So, the truth of the matter is, that topic and narrative can never both be fully explored in the same work.

And so, some writers seek a perfect structure at the expense of the passion of their topic. And others seek to completely explore their topic, though it makes a shambles of narrative.

But if you can accept that structure should not be perfect and that topic will never be expressed, then you can find the balance between the two that optimizes the effect or personal satisfaction you are shooting for.

When creating, the Muse abhors structure. She wishes to romp free in the fields of experience. You must never try to bridle the Muse or she will run away from you never to return.

So, in any first draft, forget about structure. Let the story flow of its own topical organic nature.

At this time, you create a Story World – the universe of experience in which your story will take place. It is not your story, but is the realm in which your story’s journey will occur. But it should have no structure, because it is not even a narrative yet – just the narrative space in which the narrative will eventually form.

Next, after creating a story world, you create a storyline. This can be one or more journeys across your story world, with a point of departure, a destination, and meandering around and lingering at as manny different concepts as you like within your story world. Again, structure should not be specifically applied at this time, since your own mind is already automatically laying the embryonic foundations of structure in the background while your Muse creates.

Finally, in the third stage, you look at your finished storyline journeys and, regardless if there is just one story/journey or many, you go to the list of Story Points in Dramatica and make sure each journey has them all, as completely as is reasonable.

So, you ensure there is a goal, a protagonist, a main character, an influence character unique ability, and so on. BUT do NOT create a storyform yet! We aren’t interested at this stage what kind of goal it is, just to identify what the topical subject matter of the goal is – that each journey HAS a goal.

Finally, once you have revised your storylines to include as many of the story points as you reasonably can, THEN and ONLY then do you create a storyform. This storyform will provide a template to which you can aspire, but like the pencil and the ruler, you can never really achieve without short changing your topic and your passion.

So, in seeing what KIND of goal your story SHOULD have, for example, you can then consider if your goal is actually like that, similar to that, or worlds away from that. And, if it doesn’t match exactly, you can determine if you think that will hurt your story, or if it is close enough, or the story point minor enough, that you can just leave it as it is, in the most passionate and organic form, and ignore structure at that point.

No one ever read a book or saw a movie to experience a magnificent structure. The readers and audience are there to ignite their passions about a topic of interest to them. THAT is the bottom line and it is also King. Never let structure get in the way of that.

Consider the Main Character and the Influence Character who, it would seem at first blush, are as opposite as they can be in regard to some underlying philosophical perspective, world view, belief system or moral code.

Consider the Main Character and the Influence Character who, it would seem at first blush, are as opposite as they can be in regard to some underlying philosophical perspective, world view, belief system or moral code. For fans of the Dramatica Story Structure Theory (and software):

For fans of the Dramatica Story Structure Theory (and software):

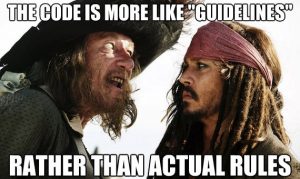

Of late, I’ve been working with the concept that perfect story structure is a myth – and should be! As they say in the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie, “it’s more of a guideline than a rule.”

Of late, I’ve been working with the concept that perfect story structure is a myth – and should be! As they say in the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie, “it’s more of a guideline than a rule.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.