Category Archives: Dramatica

Characters vs. Players

Dramatica Theory Overview (video)

First part of our class on the story structure of characters

The “Influence Character” in a Nut Shell

Stories have a mind of their own, as if they were a person in their own right in which the structure is the story’s psychology and the storytelling is its personality.

Characters, in addition to acting as real people,, also represent facets of the overall Story mind, such as the Protagonist which stands for our initiative to effect change and the Skeptic archetype which illustrates our doubt.

Yet in our own minds is a sense of self, and this quality is also present in the Story Mind as the Main Character. Every complete story has a Main Character or the readers or audience cannot identify with the story; they cannot experience the story first hand from the inside, rather than just as observers.

This Main Character does not have to be the Protagonist anymore than we only look at the world through our initiative. Sometimes, for example, we might be coming from our doubt or looking at the world in terms of our doubt. In such a story, the Main Character would be the Skeptic, not the Protagonist.

Any of the facets of our minds that are represented as characters might be the Main Character – the one through whose eyes the readers or audience experience the story. And in this way, narratives mirror our minds in which we have a sense of self (“I think therefore I am”) and it might, in any given situation, be centered on any one of our facets.

Yet there is one other special character on a par with the Main Character that is found within ourselves and, therefore, also within narrative: the Influence Character.

The Influence Character represents that “devil’s advocate “ voice within ourselves – the part of ourselves that validates our position by taking the opposing point of view so that we can gain perspective by weighing both sides of an issue. This ensures that, as much as possible, we don’t go bull-headedly along without questioning our own beliefs and conclusions.

In our own minds, we only have one sense of self – one identity. The same is true for narratives, including fictional stories. The Influence Character is not another identity, but our view of who we might become if we change our minds and adopt that opposing philosophical point of view. And so, we examine that other potential “self” to not only understand the other side of the issues, but how that might affect all other aspects or facets of ourselves. In stories, this self-examination of our potential future selves appears as the philosophical conflict and ongoing argument over points of view, act by act.

Ultimately we (or in stories, the Main Character) will either become convinced that this opposing view is a better approach or will remain convinced that our original approach is still the best choice.

No point of view is good or bad in and of itself but only in context. What is right in one situation is wrong in another. Situations, however, are complex, and often are missing complete data. And so we must rely on experience to fill in the expected pattern and to project the likely course it will take. Entertaining the opposite point of view shines a light in the shadows of our initial take on the issues. Psychologically, this greatly enhances our chances for survival.

This is why the inclusion of an Influence Character in any narrative is essential not only to fully representing the totality of our mental process but to provide a balanced look a the issues under examination by the author.

A Tale is a Statement

Part 2 of our 113 part video series on story structure

Download this video, audio or view on our web site at http://storymind.com/page104.htm

Introducing the Story Mind (video) 1 of 113 parts

Download video, audio and view on our web site at http://storymind.com/page103.htm

Dramatica: How We Did It!

New on Kindle for $2.99

Over the years people have asked how we came up with such a behemoth of a theory. When I hit 60 I figured I better spell it all out before nobody ever knows! So here it is, step by step, epiphany by epiphany (try saying that five times fast) – the unedited unvarnished truth about Dramatica’s origins and the not-quite-right parents who gave birth to it.

Writing Stories About Hopes and Dreams

A lot of people, writers included, use the words “hope” and “dream” pretty much interchangeably. Fact is, each describes a completely different way of imagining the future. Being clear not only of their definitions but of the different states of mind each invokes will not only help you better communicate with your readers or audience, but may also open a deeper level of sophistication in the message you are trying to convey.

Hope is a desired future to which at least one definitive pathway exists. It doesn’t have to be a sure thing or even a likely outcome that the hope will be achieved – just that there is at least one causal path that, if completed, will arrive at the desired future.

For example, if one hopes to graduate, it is a matter of following a laid out series of steps that, when completed, will result in a diploma.

In contrast, Dream is a desired future for which no definitive pathway exists. Dreams may be likely to be realized or may be nearly impossible, but there must be at least some possibility of being achieved or it is not a Dream but a Fantasy.

For example, if one dreams of becoming a movie star and sits around a popular restaurant for studio executives every day, there literally is no Hope, but the dream can remain alive forever.

It is important to note that the pathway to achieving a hope is not necessarily only linear. While getting a degree may require taking some course in given order (101 before 201, for example), other course are electives and the only requirement to achieve the hope is that a certain number are fulfilled, regardless of the order.

Similarly, one can try to realize a dream by taking steps, such as singling out a studio exec and stalking them, or by creating a favorable environment, such as showing up not only at a restaurant, but also at a gym and a charity fundraiser, believing that by being more visible, the odds are increased for being “noticed.”

To be a true hope, there must be a certain cause and effect relationship between the steps or conditions in which one engages and the achievement of the hope state. But a dream, by definition, is built on indirect relationships and influence, rather than certain connections.

Keep in mind that there are two kinds of causal relationships – if/then and when/also. If/then is standard temporal causality, as in One bad apple spoils the bunch. When/also is the spatial version of causality, as in Where there’s smoke, there’s fire. In each case, there is a direct connection between condition one, and condition two: If condition one is met, condition two is certain.

It is this absolute association that is not present in dreams. But from an emotional standpoint, there is no difference between hoping and dreaming. Each is a future state that is highly desired, but in hoping, one expects that future if all the conditions are met, while in dreaming, meeting the conditions provides no guarantee.

In Dramatica theory, Hope vs. Dream is a thematic conflict. It describes stories in which the message revolves around proving that in the given situation of that particular story, it is either better to hope or to dream.

Is one deluded by an intense dream into thinking there is real hope? Or, is one missing out on life experience and the rare but real advent of a lucky chance by confining oneself to only those things for which hope exists?

We’ve all seen these kinds of stories in books, movies, television and stage plays. As an author, it can improve both your work and your life to explore the difference between the two.

Here are the specific definitions of Hope and Dream from the Dramatica Dictionary:

Hope

Variation – dynamic pair: Dream ↔ Hope

a desired future if things go as expected

Hope is based on a projection of the way things are going. When one looks at the present situation and notes the direction of change, Hope lies somewhere along that line. As an example, if one is preparing for a picnic and the weather has been sunny, one Hopes for a sunny day. If it was raining for days, one could not Hope but only Dream. Still, Hope acknowledges that things can change in unexpected ways. That means that Hoping for something is not the same as expecting something. Hope is just the expectation that something will occur unless something interferes. How accurately a character evaluates the potential for change determines whether he is Hoping or dreaming. When a character is dreaming and thinks he is Hoping, he prepares for things where there is no indication they will come true.

syn. desired expectation, optimistic anticipation, confident aspiration, promise, encouraging outlook.

Dream

Variation – dynamic pair: Hope ↔ Dream

a desired future that requires unexpected developments

Dream describes a character who speculates on a future that has not been ruled out, however unlikely. Dreaming is full of “what ifs.” Cinderella dreamed of her prince because it wasn’t quite unimaginable. One Dreams of winning the lottery even though one “hasn’t got a hope.” Hope requires the expectation that something will happen if nothing goes wrong. Dreaming has no such limitation. Nothing has to indicate that a Dream will come true, only that it’s not impossible. Dreaming can offer a positive future in the midst of disaster. It can also motivate one to try for things others scoff at. Many revolutionary inventors have been labeled as Dreamers. Still and all, to Dream takes away time from doing, and unless one strikes a balance and does the groundwork, one can Dream while hopes go out the window for lack of effort.

syn. aspire, desiring the unlikely, pulling for the doubtful, airy hope, glimmer, far fetched desire

Learn more about Theme in my book:

Dramatica Tip 1 – A Better Place to Start

Both Dramatica Pro (Windows) and Dramatica Story Expert (Mac) are geared toward diving right into your story’s structure and making structural choices. But for more intuitive writers this can cause major problems.

Both Dramatica Pro (Windows) and Dramatica Story Expert (Mac) are geared toward diving right into your story’s structure and making structural choices. But for more intuitive writers this can cause major problems.

While Dramatica Pro has a “Start Here” button on the opening screen and Story Expert has a “New User” section in the opening splash screen options, DON’T GO THERE!!!

Each of these puts you directly onto a path to build your story’s structure by answering a series of questions about your story and your intent as an author and that can scuttle your story development efforts right out of the gate.

This existing approach was intended to show the power and usefulness of the interactive patented Story Engine at the heart of both programs. But an unfortunate side effect is that it also makes Dramatica appear to be incredibly complex and unfamiliar, and also requires an steep learning curve before you get comfortable with the system.

What’s more, when questions are asked such as “What is your Main Character’s Domain?” or “What is the Relationship Throughline’s Catalyst?” it is almost sure to frustrate many authors who are excited by their subject matter and ideas and just want to get started developing and improving their stories.

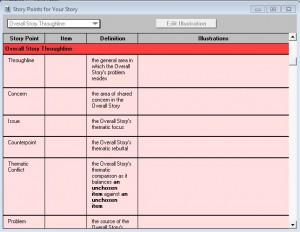

Fortunately, there is a better place to start: the Story Points Window. The Story Points Window lists all the structural elements in your story with a space to illustrate how that element will appear or come into play in your story. This ensures that there are no structural holes caused by forgetting to include an important point.

Fortunately, there is a better place to start: the Story Points Window. The Story Points Window lists all the structural elements in your story with a space to illustrate how that element will appear or come into play in your story. This ensures that there are no structural holes caused by forgetting to include an important point.

Normally the Story Points Window is used after you have already created a structural storyform using the Story Engine, and then can refer to each story point and work out how to implement it in your story. But, again, this puts structure before creativity and flies in the face of the excitement and enthusiasm of getting on with your writing.

So, the tip is to begin with the Story Points Window before making even a single structural choice! Here’s how you do it:

First, open the Story Points Window from the desktop in Dramatica Pro or from the tool bar icon in Dramatica Story Expert. You will find that it contains the names of all the story points tracked by the Story Engine, but doesn’t yet have the structural choice you made listed. (See picture above)

The first column shows the name of each story point. The second column will list your structural choice for that story point when you eventually make it. The third column provides a definition of each story point. The fourth column is where you would normally illustrate how each story point will show up in your story – but we’re going to do it differently….

Start at the top of the list of story points. The first story point is called Resolve. Its definition reads, the ultimate disposition of the Main Character to Change or Remain Steadfast.

If this story point makes sense to you in regard to your story, then in the illustration column, describe how it shows up in your story. If it doesn’t yet connect to your story, skip it and move on to the next.

The difference from the standard way the software says you should go about things is that you don’t have to first make the structural choices directly from all the ideas you have floating around in your head. Rather, first you focus on a story point and describe how it applies to your story’s subject matter, rather than to your structure. Then later you’ll go back and make the structural choices, but when you do, you’ll see what you’ve already written in the Illustration column and the choice will be much easier to make.

As an example of this, you’ll come across a story point called Overall Story Domain which is defined as the general area in which the Overall Story’s problem resides. If you do it Dramatica’s way, you are asked to choose which of four items best describes your Overall Story’s Domain: Situation, Activity, Attitude or Manipulation.

Now that can be a tough choice to make if you haven’t studied exactly what each of these terms means. And trying to get into a mind set where you can sort through all the material you have swirling around in your head about your story to find the answer to that question can sometimes be impossible.

But if you forget about the actual structural choices until later and instead just describe in plain language the general area in which the Overall Story’s problem resides you might write something like, My story’s problem is about traveling to the underworld to recover a talisman that will prevent an alien invasion , then later it will be a lot easier to say, “Well, that is more an Activity than a Situation, Attitude or Manipulation.” Entering the subject matter first makes the structural choice easier later.

So, go through the entire list of Story Points and when you reach the bottom, go through the list one more time and see if you can now write something about the story points you left blank the first time around. Why? Because sometimes the process of organizing your thoughts and getting your ideas out of your head is enough to open new insights.

Once you’ve filled in all the illustrations you can, then go to the Story Guide which is the step by step set of structural questions. You can find it as a button on the Dramatica Pro desktop or in the tool bar icons in Story Expert.

Now, when you go to a structural question, instead of having to face it directly, you’ll find that the illustrations you put in the Story Points window automatically show up on each structural question. So, you can refer to that material and make the structural choice that best describes it. And, of course, you can also revise your illustrations as you go – as you come to know your story better.

Using this method, you’ll never have to run into the wall of structure, but can follow your Muse and then describe what she had told you.

Dramatica Trivia 2

Before the Dramatica software was released – before the theory was completed, we ran into a road block. We had completed the 3-D version of the model and were trying to plot the progression of various stories in each quad to see if we could find patterns of sequence that could predict how a story should unfold.

Though we could see circular patterns in some quads, Z patterns in others, and hairpin patterns in others, they varied from quad to quad and story to story, not only in placement but in the direction in which events progressed along the patterns through each quad.

In short, we were going nuts trying to understand something that felt like it made sense but appeared to be completely chaotic. This was a very depressing time – to get so far and be stuck for so long. And then, one weekend, I took my daughter to the Museum of Science and Industry at Exposition Park in Los Angeles.

There was an exhibit of hands-on science experiments for children. One of these was a row of 21 bar magnets on spindles. You would turn one magnet and the one next to it would turn in response, and so on, until eventually you could get all 21 turning in sync at once.

While we were using this, it struck me – the patterns in the model weren’t to be understood by plotting them on the chart. Rather, all patterns were really just circular around the quad, but the pressures that built tension in a story flipped and rotated the items in a quad, and that each quad affected the ones around it like the row of magnets did.

Armed with this epiphany, I returned to the model and began to write the algorithms the ultimately came to drive the story engine.

You must be logged in to post a comment.