Author Archives: Melanie Anne Phillips

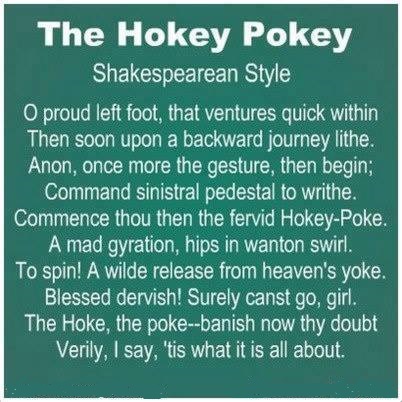

The Hokey Pokey, Shakespearean Style

Writing Tip: How talented do you have to be?

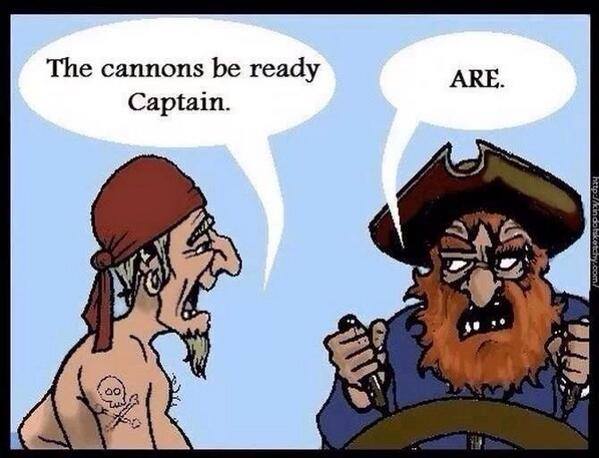

Writing Pirate Grammar…

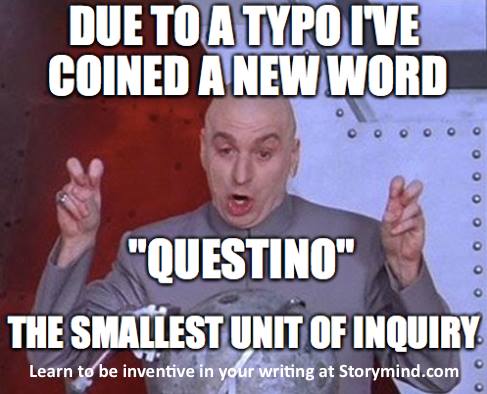

Creative Writing: Coining A Word

If you can’t get all your story ideas to fit together…

I don’t know what I’m writing about!

Work Stories vs. Dilemma Stories

What follows is an excerpt from an early unpublished draft of the book that ultimately became, Dramatica: A New Theory of Story. This section explores the difference between stories that just require effort and those that require choosing the lesser of two evils.

Problems

Without a problem, the Dramatica Model, like the mind it represents, is at rest or Neutral. All of the pieces within the model are balanced and no dramatic potential exists. But when a problem is introduced, that equilibrium becomes unbalanced. We call that imbalance an Inequity. An inequity provides the impetus to drive the story forward and causes the Story Mind to start the problem solving process.

Work Stories and Dilemma Stories

In Dramatica, we differentiate between solvable and unsolvable problems. The solvable problem is, simply, a problem. Whereas an unsolvable problem is called a Dilemma. In stories, as in life, we cannot tell at the beginning whether a problem is solvable or not because we cannot know the future. Only by going through the process of problem solving can we discover if the problem can be solved at all.

If the Problem CAN be solved, though the effort may be difficult or dangerous, and in the end we DO succeed by working at it, we have a Work Story. But if the Problem CAN’T be solved, in the case of a Dilemma, once everything possible has been tried and the Problem still remains, we have a Dilemma Story.

Read the entire unpublished draft here.

Read the free online edition of Dramatica – A New Theory of Story in its final form.

Get a paperback of the published version for easy reference on Amazon.

Work Stories and Dilemma Stories

What follows is an excerpt from an early unpublished draft of the book that ultimately became, Dramatica: A New Theory of Story. This section explores the difference between work stories in which the characters must simply overcome obstacles to succeed and dilemma stories, in which characters must change their perspectives if they are to succeed.

*

Problems

Without a problem, the Dramatica Model, like the mind it represents, is at rest or Neutral. All of the pieces within the model are balanced and no dramatic potential exists. But when a problem is introduced, that equilibrium becomes unbalanced. We call that imbalance an Inequity. An inequity provides the impetus to drive the story forward and causes the Story Mind to start the problem solving process.

Work Stories and Dilemma Stories

In Dramatica, we differentiate between solvable and unsolvable problems. The solvable problem is, simply, a problem. Whereas an unsolvable problem is called a Dilemma. In stories, as in life, we cannot tell at the beginning whether a problem is solvable or not because we cannot know the future. Only by going through the process of problem solving can we discover if the problem can be solved at all.

If the Problem CAN be solved, though the effort may be difficult or dangerous, and in the end we DO succeed by working at it, we have a Work Story. But if the Problem CAN’T be solved, in the case of a Dilemma, once everything possible has been tried and the Problem still remains, we have a Dilemma Story.

Mind and Universe

At the most basic level, all problems are the result of inequities between Mind (ourselves) and Universe (the environment). When Mind and Universe are in balance, they are in Equity and there is neither a problem nor a story. When the Mind and Universe are out of balance, and Inequity exists between them, there is a problem and a story to be told about solving that problem.

Example: Jane wants a new leather jacket that costs $300.00. She does not have $300.00 to buy the jacket. We can see the Inequity by comparing the state of Jane’s Mind (her desire for the new jacket) to the state of the Universe (not having the jacket).

Note that the problem is not caused soley by Jane’s desire for a jacket, nor by the physical situation of not having one, but only because Mind and Universe are unbalanced. In truth, the problem is not with one or the other, but between the two.

There are two ways to remove the Inequity and resolve the problem. If we change Jane’s Mind and remove her desire for the new jacket — no more problem. If we change the Universe and supply Jane with the new jacket by either giving her the jacket or the money to buy it — no more problem. Both solutions balance the Inequity.

Subjective and Objective Views

From an outside or objective point of view, one solution is as good as another. Objectively, it doesn’t matter if Jane changes her Mind or the Universe changes its configuration so long as the inequity is removed.

However, from an inside or subjective point of view, it may matter a great deal to Jane if she has to change her Mind or the Universe around her to remove the Inequity. Therefore, the subjective point of view differs from the objective point of view in that personal biases affect the evaluation of the problem and the solution. Though objectively the solutions have equal weight, subjectively one solution may appear to be better than another.

Stories are useful to us as an audience because they provide both the Subjective view of the problem and the Objective view of the solution that we cannot see in real life. It is this Objective view that shows us important information outside our own limited perspective, providing a sense of the big picture and thereby helping us to learn how to handle similar problems in our own lives.

If the Subjective view is seen as the perspective of the soldier in the trenches, the Objective view would be the perspective of the General watching the engagement from a hill above the field of battle. When we see things Objectively, we are looking at the Characters as various people doing various things. When we are watching the story Subjectively, we actually stand in the shoes of a Character as if the story were happening to us.

A story provides both of these views interwoven throughout its unfolding. This is accomplished by having a cast of Objective Characters, and also special Subjective Characters. The Objective Characters serve as metaphors for specific methods of dealing with problems. The Subjective Characters serve as metaphors for THE specific method of dealing with problems that is crucial to the particular problem of that story.

*

Read the entire unpublished draft here.

Read the free online edition of Dramatica – A New Theory of Story in its final form.

Get a paperback of the published version for easy reference on Amazon.

A Story Mind

What follows is an excerpt from an early unpublished draft of the book that ultimately became, Dramatica: A New Theory of Story. This section introduces the concept of a Story Mind – the notion that characters, plot, theme, and genre are all facets of a larger super mind that is the structure of the story itself

*

Stories have traditionally been viewed as a series of events affecting independently-acting characters — but not to Dramatica. Dramatica sees every character, conflict, action or decision as aspects of a single mind trying to solve a problem. This mind, the Story Mind,™ is not the mind of the author, the audience, nor any of the characters, but of the story itself. The process of problem solving is the unfolding of the story.

But why a mind? Certainly this was not the intent behind the introduction of stories as an art form. Rather, from the days of the first storytellers right up through the present, when a technique worked, it was repeated and copied and became part of the “conventions” of storytelling. Such concepts as the Act and the Scene, Character, Plot and Theme, evolved by such trial and error.

And yet, the focus was never on WHY these things should exist, but how to employ them. The Dramatica Theory states that stories exist because they help us deal with problems in our own lives. Further, this is because stories give us two views of the problem.

One view is through the eyes of a Main Character. This is a Subjective view, the view FROM the Story Mind as it deals with the problem. This is much like our own limited view or our own problems.

But stories also provide us with the Author’s Objective view, the view OF the story mind as it deals with a problem. This is more like a “God’s eye view” that we don’t have in real life.

In a sense, we can relate emotionally to a story because we empathize with the Main Character’s Subjective view, and yet relate logically to the problem through the Author’s Objective view.

This is much like the difference between standing in the shoes of the soldier in the trenches or the general on the hill. Both are watching the same battle, but they see it in completely different terms.

In this way, stories provide us with a view that is akin to our own attempt to deal with our personal problems while providing an objective view of how our problems relate to the “Bigger Picture”. That is why we enjoy stories, why they even exist, and why they are structured as they are.

Armed with this Rosetta Stone concept we spent 12 years re-examining stories and creating a map of the Story Mind. Ultimately, we succeeded.

The Dramatica Model of the Story Mind is similar to a Rubik’s Cube. Just as a Rubik’s Cube has a finite number of pieces, families of parts (corners, edge pieces) and specific rules for movement, the Dramatica model has a finite size, specific natures to its parts, coordinated rules for movement, and the possibility to create an almost infinite variety of stories — each unique, each accurate to the model, and each true to the author’s own intent.

The concept of a limited number of pieces frequently precipitates a “gut reaction” that the system must itself be limiting and formulaic. Rather, without some kind of limit, structure cannot exist. Further, the number of parts has little to do with the potential variety when dyanmics are added to the system. For example, DNA has only FOUR basic building blocks, and yet when arranged in the dyamic matrix of the double helix DHN chain, is able to create all the forms of life that inhabit the planet.

The key to a system that has identity, but not at the expense of variety, is a flexible structure. In a Rubik’s cube, corners stay corners and edges stay edges no matter how you turn it. And because all the parts are linked, when you make a change on the side you are concentrating on, it makes appropriate changes on the sides of the structure you are not paying attention to.

And THAT is the value of Dramatica to an author: that it defines the elements of story, how they are related and how to maipulate them. Plot, Theme, Character, Conflict, the purpose of Acts, Scenes, Action and Decision, all are represented in the Dramatica model, and all are interrelated. It is the flexible nature of the structure that allows an author to create a story that has form without formula.

*

Read the entire unpublished draft here.

Read the free online edition of Dramatica – A New Theory of Story in its final form.

Get a paperback of the published version for easy reference on Amazon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.