This article was originally written as part of an early draft of our book on the Dramatica theory of narrative which but was never included. It seeks to describe how characters come to misunderstand each other, and how this can lead to conflict.

I’m reprinting it here due to the really useful concepts it brings to light, but bear in mind that many of the terms have evolved since then and many of the notions have been significantly refined over the years.

Here’s the gist, and then the article:

All of our understandings of each other are based on the narratives we create to get a grip on what someone’s intent is, and what their future behavior is likely to be. Basically, we want to know what they mean by what they say, and what they are likely to do.

But trying to grasp someone else’s meaning is an interpretive art. And in addition, we all have our own blinders on – our own expectations based on a history of interactions, both with the specific individual with whom we are communicating and with other people, both similar and no so much, gathered over the course of our lives.

In the article that follows, I use the word “justification” to describe how those past experiences add up to expectations, pre-judgments and even blind spots that keep us from seeing what’s really going on or even warp it to convince us things are quite different – even opposite – of what someone really intended or intended to do.

Here is the original text:

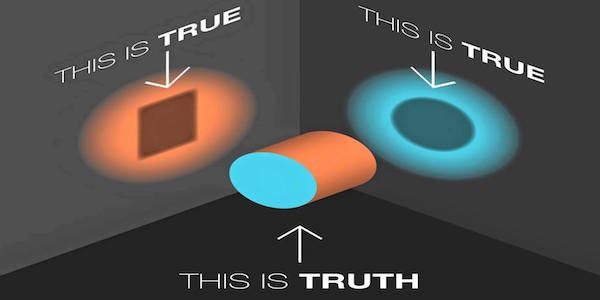

What is Justification? Justification is a state of mind wherein the Subjective view differs from the Objective view. Okay, fine. But how about in plain English!!!! Very well, when someone sees things differently than they are, they are Justifying. This can happen either because the mind draws a wrong conclusion or assumes, or because things actually change in a way that is no longer consistent with a held view.

All of this comes down to cause and effect. For example, suppose you have a family with a husband, wife and young son. Here is a sample backstory of how the little boy might develop a justification that could plague him in later life….

The husband works at a produce stand. Every Friday he gets paid. Also every Friday a new shipment of fresh beets comes in. So, every Friday night, he comes home with the beets and the paycheck. The paycheck is never quite enough to cover the bills and this is eating the wife alive. Still, she knows her husband works hard, so she tries to keep her feelings to herself and devotes her attention to cooking the beets.

Nevertheless, she cannot hold out for long, and every Friday evening at some point while they eat, she and her husband get in an argument. Of course, like most people who are trying to hold back the REAL cause of her feelings, she picks on other issues, so the arguments are all different

This short description lays out a series of cause and effect relationships that establish a justification. With this potential we have wound up the spring of our dramatic mechanism. And now we are ready to begin our story to see how that tension unwinds.

The Story Begins: The young boy, now a grown adult with a wife and child of his own, sits down to dinner with his family. He begins to get belligerent and antagonistic. His wife does not know what she has done wrong. In fact, later, he himself cannot say why he was so upset. WE know it is because his wife served beets.

It is easy to see that from the young boy’s knowledge of the situation when he was a child, the only visible common element between his parent’s arguments and his environment was the serving of beets. They never argued about the money directly, and that would probably have been beyond his ken anyway.

Obviously, it is not stupidity that leads to misconceptions, but lack of information. The problem is, we have no way of knowing if we have enough information or not, for we cannot determine how much we do not know. It is a human trait, and one of the Subjective Characters as well, to see repetitive proximities between two items or between an item and a process and assume a causal relationship.

But why is this so important to story? Because that is why stories exist in the first place! Stories exist to show us a greater Objective truth that is beyond our limited Subjective view. They exist to show us that if we feel something is a certain way, even based on extensive experience, it is possible that it really is not that way at all.

For the Pivotal Character, it will be shown that the way she believed things to be really IS the way they are in spite of evidence to the contrary. The message here is that our understanding is sometimes not limited by past misconceptions, but by lack of information in the present. “Keeping the faith” describes the feeling very well. Even in the face of major contradiction, holding on to one’s views and dismissing the apparent reality as an illusion or falsehood.

For the Primary Character, it will be shown that things are really different than believed and the only solution is to alter one’s beliefs. This message is that we must update our understanding in the light of new evidence or information. “Changing one’s faith” is the issue here.

In fact, that is what stories are all about: Faith. Not just having it, but also learning if it is valid or not. That is why either Character, Pivotal or Primary, must make a Leap of faith in order to succeed. At the climax of a story, the need to make a decision between remaining steadfast in one’s faith or altering it is presented to both Pivotal and Primary Characters. EACH must make the choice. And each will succeed or fail.

The reason it is a Leap of Faith is because we are always stuck with our limited Subjective view. We cannot know for sure if the fact that evidence is mounting that change would be a better course represents the pangs of Conscience or the tugging of Temptation. We must simply decide based on our own internal beliefs.

If we decide with the best available evidence and trust our feelings we will succeed, right? Not necessarily. Success or failure is just the author’s way of saying she agrees or disagrees with the choice made. Just like real life stories we hear every day of good an noble people undeservedly dying or losing it all, a Character can make the good and noble choice and fail. This is the nature of a true Dilemma: that no matter what you do, you lose. Of course, most of us read stories not to show us that there is no fairness in the impartial Universe (which we see all too much of in real life) but to convince ourselves that if we are true to the quest and hold the “proper” faith, we will be rewarded. It really all depends on what you want to do to your audience.

A story in which the Main Character is Pivotal will have dynamics that lead the audience to expect that remaining Steadfast will solve the problem and bring success. Conversely, a story in which the Main Character is Primary will have differently dynamics that lead the audience to expect that Changing will solve the problem and bring success. However, in order to make a statement about real life outside of the story, the Author may violate this expectation for propaganda or shock purposes.

For example, if, in Star Wars, Luke had made the same choice and turned off his targeting computer (trusting in the force), dropped his bombs, and missed the target, Darth blows him up and the Death Star obliterates the rebels… how would we feel? Sure you could write it that way, but would you want to? Perhaps! Suppose you made Star Wars as a government sponsored entertainment in a fascist regime. That might very WELL be the way you would want to end it!

The point being, that to create a feeling of “completion” in an audience, if the Main Character is Pivotal, she MUST succeed by remaining Steadfast, and a Primary Main Character MUST change.

Now, let’s take this sprawling embryonic understanding of Justification and apply it specifically to story structure.

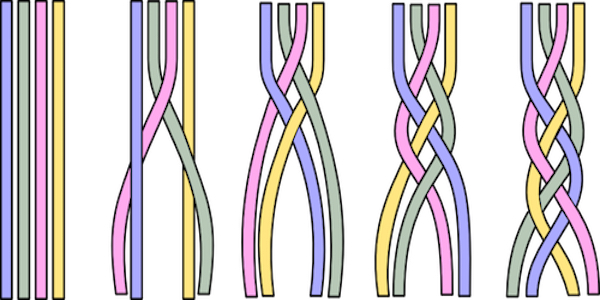

The Dramatica Model is built on the process of noting that an inequity exists, then comparing all possible elements of Mind to Universe until the actual nature of the inequity is located, then making a Leap of Faith to change approach or remain steadfast.

At the most basic level, we have Mind and we have Universe, as indicated in the introduction to this book. An inequity is not caused solely by one or the other but by the difference between the two. So, an inequity is neither in Mind nor Universe, but between them.

However, based on their past experiences (assumed causal relationships in backstory) a given Subjective Character will choose either Mind or Universe as the place to attempt to resolve the inequity. In other words, she decides that she likes one area the way it is, and would rather change the other. As soon as this decision is made, the inequity becomes a problem because it is seen in one world or the other. i.e.: “There is a problem with my situation I have to work out.” or “I have to work out a personal problem”.

Doesn’t a Character simply see that the problem is really just an inequity between Mind and Universe? Sure, but what good does that do them? It is simply not efficient to try to change both at the same time and meet halfway. Harking back to our introductory example of Jane who wanted a $300 jacket: Suppose Jane decided to try and change her mind about wanting the jacket even while going out and getting a job to earn the money to buy it. Obviously, this would be a poor plan, almost as if she were working against herself, and in effect she would be. This is because it is a binary situation: either she has a jacket or she does not, and, either she wants a jacket or she does not. If she worked both ends at the same time, she might put in all kinds of effort and end up having the jacket not wanting it. THAT would hardly do! No, to be efficient, a Character will consciously or responsively pick one area or the other in which to attempt to solve the problem, using the other area as the measuring stick of progress.

So, if a Main Character picks the Universe in which to attempt a solution, she is a “Do-er” and it is an Action oriented story. If a Main Character picks the Mind in which to attempt a solution, she is a “Be-er” and it is a Decision oriented story. Each story has both Action and Decision, for they are how we compare Mind against Universe in looking for the inequity. But an Action story has a focus on exploring the physical side and measuring progress by the mental, where as a Decision story focuses on the mental side and measures progress by the physical.

Whether a story is Action or Decision has nothing to do with the Main Character being Pivotal or primary. As we have seen, James Bond has been both. And in the original “Raiders of the Lost Ark”, Indy must change from his disbelief of the power of the ark and its supernatural aspects in order to succeed by avoiding the fate that befalls the Nazis – “Close your eyes, Marian; don’t look at it!”

Action or Decision simply describes the nature of the problem solving process, not whether a character should remained steadfast or change. And regardless of which focus the story has, a Pivotal Character story has dynamics indicating that remaining steadfast is the proper course. That mean that in an Action story, a Pivotal Character will have chosen to solve the problem in the Universe and must maintain that approach in the face of all obstacles in order to succeed. In a Decision story, a Pivotal Character will have chosen to solve the problem in the Mind, and must maintain that approach to succeed. On the other hand, a Primary Character, regardless of which world she selects to solve the problem, will discover she chose the wrong one, and must change to the other to find the solution.

A simple way of looking at this is to see that a Pivotal Character must work at finding the solution, and if diligent will find it where she is looking. She simply has to work at it. In Dramatica, when a Pivotal Character is the Main Character, we call it a Work Story (which can be either Action or Decision)

A Primary Character works just as hard as the Pivotal to find the solution, but in the end discovers that the problem simply cannot be solved in the world she chose. She must now change and give up her steadfast refusal to change her “fixed” world in order to overcome the log jam and solve the problem. Dramatica calls this a Dilemma story, since it is literally impossible to solve the problem in the manner originally decided upon.

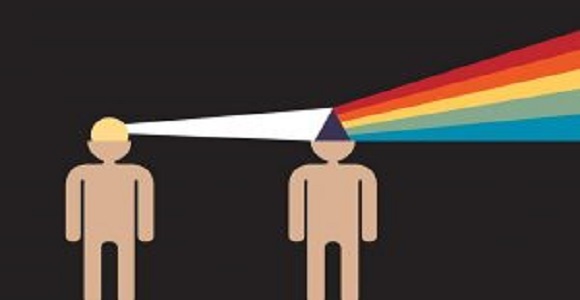

From the Subjective view, both Pivotal and Primary work at solving the problem. Also, each is confronted with evidence suggesting that they must change. This evidence is manifested in increasingly growing obstacles they both must overcome. So what makes the audience want one character to remain steadfast and the other to change?

The Objective view.

Remember, we have two views of the Story Mind. The Subjective is the limited view in which the audience, in empathy with the Main Character, simply does not have enough information to decide whether or not to change. But then, unlike the Main Character, the audience is privy to the Objective view which clearly shows (by the climax) which would be the proper choice. To create a sense of equity in the audience, if the Main Character’s Subjective Choice is in line with the Objective View, they must succeed. But if a propaganda or shock value is intended, an author may choose to have either the proper choice fail or the improper choice succeed.

This then provides a short explanation of the driving force behind the unfolding of a story, and the function of the Subjective Characters. Taken with the earlier chapters on the Objective Characters, we now have a solid basic understanding of the essential structures and dynamics that create and govern Characters.

Learn more about Dramatica

and learn more about Narrative Science

You must be logged in to post a comment.