In this episode of my 113 part course on story structure from 1999, I discuss the difference between a “tale” and a “story,” beginning with the notion that “a tale is a statement and a story is an argument.

In this episode of my 113 part course on story structure from 1999, I discuss the difference between a “tale” and a “story,” beginning with the notion that “a tale is a statement and a story is an argument.

As with people, your story’s mind has different aspects. These are represented in your Genre, Theme, Plot, and Characters. Genre is the overall personality of the Story Mind. Theme represents its troubled value standards. Plot describes the methods the Story Mind uses as it tries to work out its problems. Characters are the conflicting drives of the Story Mind.

Genre

To an audience, every story has a distinct personality, as if it were a person rather than a work of fiction. When we first encounter a person or a story, we tend to classify it in broad categories. For stories, we call the category into which we place its overall personality its Genre.

These categories reflect whatever attributes strike us as the most notable. With people this might be their profession, interests, attitudes, style, or manner of expression, for example. With stories this might be their setting, subject matter, point of view, atmosphere, or storytelling.

We might initially classify someone as a star-crossed lover, a cowboy, or a practical joker who likes to scare people. Similarly, we might categorize a story as a Romance, a Western, or a Horror story.

As with the people we meet, some stories are memorable and others we forget as soon as they are gone. Some are the life of the party, but get stale rather quickly. Some initially strike us as dull, but become familiar to the point we look forward to seeing them again. This is all due to what someone has to say and how they go about saying it.

The more time we spend with specific stories or people the less we see them as generalized types and the more we see the traits that define them as individuals. So, although we might initially label a story as a particular Genre, we ultimately come to find that every story has its own unique personality that sets it apart from all others in that Genre, in at least a few notable respects.

Theme

Everyone has value standards, and the Story Mind has them as well. Some people are pig-headed and see issues as cut and dried. Others are wishy-washy and flip-flop on the issues. The most sophisticated people and stories see the pros and cons of both sides of a moral argument and present their conclusions in shades of gray, rather than in simple black & white. All these outlooks can be reflected in the Story Mind.

No matter what approach or which specific value is explored, the key structural point about value standards is that they are all comprised of two parts: the issues and one’s attitude toward them. It is not enough to only have a subject (abortion, gay rights, or greed) for that says nothing about whether they are good, bad, or somewhere in between. Similarly, attitudes (I hate, I believe in, or I don’t approve of) are meaningless until they are applied to something.

An attitude is essentially a point of view. The issue is the object under observation. When an author determines what he wants to look at it and from where he wants it to be seen, he creates perspective. It is this perspective that comprises a large part of the story’s message.

Still, simply stating one’s attitudes toward the issues does little to convince someone else to see things the same way. Unless the author’s message is preaching to the audience’s choir, he’s going to need to convince them to share his attitude. To do this, he will need to make a thematic argument over the course of the story which will slowly dislodge the audience from their previously held beliefs and reposition them so that they adopt the author’s beliefs by the time the story is over.

Plot

Novice authors often assume the order in which events transpire in a story is the order in which they are revealed to the audience, but these are not necessarily the same. Through exposition, an author unfolds the story, dropping bits and pieces that the audience rearranges until the true meaning of the story becomes clear. This technique involves the audience as an active participant in the story rather than simply being a passive observer. It also reflects the way people go about solving their own problems.

When people try to work out ways of dealing with their problems they tend to identify and organize the pieces before they assemble them into a plan of action. So, they often jump around the timeline, filling in the different steps in their plan out of sequence as they gather additional information and draw new conclusions.

In the Story Mind, both of these attributes are represented as well. We refer to the internal logic of the story – the order in which the events in the problem solving approach actually occurred – as the Plot. The order in which the Story Mind deals with the events as it develops its problem solving plan is called Storyweaving.

If an author blends these two aspects together, it is very easy miss holes in the internal logic because they are glossed over by smooth exposition. By separating them, an author gains complete control of the progression of the story as well as the audience’s progressive experience

Characters

If Characters represent the conflicting drives in our own minds yet they each have a personal point of view, where is out sense of self represented in the Story Mind? After all, every real person has a unique point of view that defines his or her own self-awareness.

In fact, there is one special character in a story that represents the Story Mind’s identity. This character, the Main Character, functions as the audience position in the story. He, she or it is the eye of the story – the story’s ego.

In an earlier tip I described how we might look at characters by their dramatic function, as seen from the perspective of a General on a hill. But what if we zoomed down and stood in the shoes of just one of those characters, we would have a much more personal view of the story from the inside looking out.

But which character should be our Main Character? Most often authors select the Protagonist to represent the audience position in the story. This creates the stereotypical Hero who both drives the plot forward and also provides the personal view of the audience. There is nothing wrong with this arrangement but it limits the audience to always experiencing what the quarterback feels, never the linemen or the water boy.

In real life we are more often one of the supporting characters in an endeavor than we are the leader of the effort. If you have always made your Protagonist the Main Character, you have been limiting your possibilities.

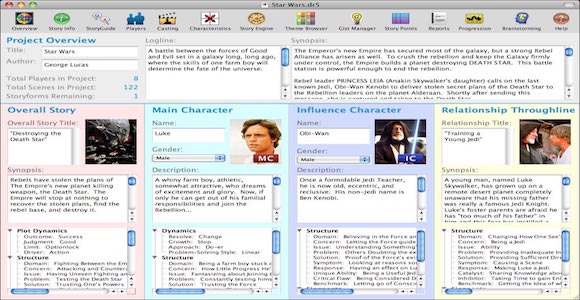

The Story Mind concept is at the heart of our

Dramatica Story Structuring Software

The Story Mind concept is a way of visualizing story structure that sees every story as having a mind of its own and the characters within it as facets of that overall mind. So, one character represents the Intellect of the Story Mind and another functions as its Skepticism, for example.

Of course, this is just at a structural level – the mechanics of the story. Naturally, characters also have to be real people in their own right so the readers or audience can identify with them.

But, structurally, the archetypes we see in stories are very like the basic mental attributes we all possess, made tangible as avatars of the Story Mind’s thought processes.

Well, that’s a pretty radical concept. So before asking any writer to invest his or her time in a concept as different as the Story Mind, it is only fair to provide an explanation of why such a thing should exist. To do this, let us look briefly into the nature of communication between an author and an audience and see if there is supporting evidence to suggest that character archetypes are facets of a greater Story Mind.

When an author tells a tale, he simply describes a series of events that both makes sense and feels right. As long as there are no breaks in the logic and no mis-steps in the emotional progression, the structure of the tale is sound.

Now, from a structural standpoint, it really doesn’t matter what the tale is about, who the characters are, or how it turns out. The tale is just a truthful or fictional journey that starts in one situation, travels a straight or twisting path, and ends in another situation.

The meaning of a tale amounts to a statement that if you start from “here,” and take “this” path, you’ll end up “here.” The message of a tale is that a particular path is a good or bad one, depending on whether the ending point is better or worse than the point of departure.

This structure is easily seen in the vast majority of familiar fairy “tales.” Tales have been used since the first storytellers practiced their craft. In fact, many of the best selling novels and most popular motion pictures of our own time are simple tales, expertly told.

In a structural sense, tales have power in that they can encourage or discourage audience members from taking particular actions in real life. The drawback of a tale is that it speaks only in regard to that specific path.

But in fact, there are many paths that might be taken from a given point of departure. Suppose an author wants to address those as well, to cover all the alternatives. What if the author wants to say that rather than being just a good or bad path, a particular course of action the best or worst path of all that might have been taken?

Now the author is no longer making a simple statement, but a “blanket” statement. Such a blanket statement provides no “proof” that the path in question is the best or worst, it simply says so. Of course, an audience is not likely to be moved to accept such a bold claim, regardless of how well the tale is told.

In the early days of storytelling, an author related the tale to his audience in person. Should he aspire to wield more power over his audience and elevate his tale to become a blanket statement, the audience would no doubt cry, “Foul!” and demand that he prove it. Someone in the audience might bring up an alternative path that hadn’t been included in the tale.

The author might then counter that rebuttal to his blanket statement by describing how the path proposed by the audience was either not as good or better (depending on his desired message) than the path he did include.

One by one, he could disperse any challenges to his tale until he either exhausted the opposition or was overcome by an alternative he couldn’t dismiss.

But as soon as stories began to be recorded in media such as song ballads, epic poems, novels, stage plays, screenplays, teleplays, and so on, the author was no longer present to defend his blanket statements.

As a result, some authors opted to stick with simple tales of good and bad, but others pushed the blanket statement tale forward until the art form evolved into the “story.”

A story is a much more sophisticated form of communication than a tale, and is in fact a revolutionary leap forward in the ability of an author to make a point. Simply put, when creating a story, and author starts with a tale of good or bad, expands it to a blanket statement of best or worst, and then includes all the reasonable alternatives to the path he is promoting to preclude any counters to his message. In other words, while a tale is a statement, a story becomes an argument.

Now this puts a huge burden of proof on an author. Not only does he have to make his own point, but he has to prove (within reason) that all opposing points are less valid. Of course, this requires than an author anticipate any objections an audience might raise to his blanket statement. To do this, he must look at the situation described in his story and examine it from every angle anyone might happen to take in regard to that issue.

By incorporating all reasonable (and valid emotional) points of view regarding the story’s message in the structure of the story itself, the author has not only defended his argument, but has also included all the points of view the human mind would normally take in examining that central issue. In effect, the structure of the story now represents the whole range of considerations a person would make if fully exploring that issue.

In essence, the structure of the story as a whole now represents a map of the mind’s problem solving processes, and (without any intent on the part of the author) has become a Story Mind.

And so, the Story Mind concept is not really all that radical. It is simply a short hand way of describing that all sides of a story must be explored to satisfy an audience. And, and if this is done, the structure of the story takes on the nature of a single character.

Learn more about the Story Mind

The Main Character represents the audience’s position in the story. Therefore, whether he or she changes or not has a huge impact on the audience’s story experience and the message you are sending to it.

Some Main Characters grow to the point of changing their nature or attitude regarding a central personal issue like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol. Others grow in their resolve, holding onto their nature or attitude against all obstacles like Dr. Richard Kimble in The Fugitive.

Change can be good if the character is on the wrong track to begin with. It can also be bad if the character was on the right track. Similarly, remaining Steadfast is good if the character is on the right track, but bad if he is misguided or mistaken.

Think about the message you want to send to your audience, and whether the Main Character’s path should represent the proper or improper way of dealing with the story’s central issue. Then select a changing or steadfast Main Character accordingly.

Excerpted from our Dramatica Story Structure Software

Try it risk-free for 90 days at Storymind.com

Every story has a core – that concept at the center that pulls all of the story elements into a cohesive whole, establishes meaning and message, and provides the story with an overall identity.

There are four fundamental kinds of cores, though each has endless variations.

1. Universe stories that are all about a fixed situation people must grapple with, such as being stuck in an overturned ocean liner, locked in a high-rise building with terrorists, being handcuffed to a murder, being the only member of a group with a particular gender or race, having a physical deformity.

2. Mind Stories that are all about fixed mind sets such as exploring or overcoming prejudice, belief in something that defies all evidence to the contrary, an unreasonable fear, a determination to accomplish something even if the reason for doing it has vanished.

3. Physics stories that are all about activities such as a trek through the jungle to obtain a lost treasure, the attempt to build the first self-aware artificial intelligence, a race across a continent in the 1800s, the effort to find a cure for a virulent new disease.

4. Psychology stores that are all the the thinking process, such as trying to come to terms with personal loss, grappling with issues of faith, overcoming addiction, growing to become a true leader.

Which of these four kinds of cores best describes what you want your story to be about and how you want it to feel?

By picking a core, you will have a central defining vision for your story that will keep it on track during development, and your completed story will come across with a powerful unified impact on your readers or audience.

The “Core” concept is part of the Dramatica Theory of Narrative Structure

Read the Dramatica Theory Book for Free in PDF

Try Dramatica Story Structuring Software risk-free for 90 days

Excerpted from the Book “Dramatica Unplugged“

By Melanie Anne Phillips, Co-creator of Dramatica

Who is your audience? And for that matter, does a single story structure affect all audience members equally? Let’s find out….

In Dramatica, there are some story points that deal directly with the structure and others that pertain to the collective impact of a number of story points. Audience Reach is one of these combined dramatics. It is also called an Audience Story

Point because it is concerned with the kind of reach the story has into the audience.

Specifically, it describes whether your readers/audience will empathize or sympathize with your Main Character. Empathy is when your readers/audience identify with your Main Character. Sympathy is when they care about your main character but feel more as if they are standing right behind the character, rather than in its shoes.

When audience members empathize, they suspend their disbelief and emotionally occupy the Main Character’s position in the story. When audience members sympathize, it seems to them as if the emotional maelstrom of the story revolves around the Main Character, making him or her the Central character of the story.

Audience Reach is determined by the effects of two story points: Story Limit and Main Character Mental Sex. Limit describes the story dynamics that force the story to a conclusion. Mental Sex describes whether your Main Character thinks like a man or a woman.

Story Limit has two variations – Time Lock and Option Lock. Time Lock stories are like the motion picture “48 Hours” in which a police detective has exactly two days before he has to return to jail a convict who is the key to solving another crime. When the time is up, the story reaches its conclusion.

Option Lock stories are similar to Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast” in which a transformed prince must make someone love him before the last petal falls from an enchanted rose or he will remain a beast forever. When the last petal falls, the conclusion is reached.

Main Character Mental Sex also has two variations – Male and Female. Mental Sex does not refer to the physical gender of the Main Character but only to its mental gender. (Because none of us truly know how the opposite sex thinks, authors often can’t help but write all of their characters as thinking in their own sex, regardless of the character’s physical gender.)

Examples can be seen in the motion picture “Aliens” in which the Main Character (Ripley) was actually written for a man and changed only the character’s dialog when the role was cast with Sigourney Weaver. Alternatively, in the movie “The Hunt for Red October”, Jack Ryan is a female mental sex Main Character as he solves problems intuitively and emotionally, rather than by observation and logic. As one might expect, male and female readers/audience members empathize or sympathize with a Main Character for different reasons.

For men, they will empathize with Male Mental Sex Main Characters and sympathize with Female Mental Sex Main Characters, regardless of which limit is

invoked – time lock or option lock. Conversely, women will empathize in an option lock but only sympathize in a time lock, regardless of what mental sex the Main Character possesses.

Why the difference? Well, the reasons are in the physiology of the brain, and too deep to go into here. If you are really interested, you’ll find a complete description of what causes the mental differences between mean and women later in this program in a lesson devoted specifically to mental sex.

Still, for a quick visual, imagine a plain old clock face. Imagine that men’s minds sit at noon, and women at 9 o’clock. Thinking clockwise, men see women as being three quarters of an hour away. Women see men as only being one quarter of an hour away. This serves to illustrate that the sexes really aren’t opposite, but are more accurately sideways to each other.

When men and women converse, they are often speaking apples and oranges and are not really in conflict or disagreement. They simply don’t have a means of seeing things the way the other sex does. So, it is not surprising that men’s empathies might be drawn to those who think like them (also at noon on the clock) while women (seeing men as just one quarter hour away) would be more affected by the situation in which the main character finds itself. For women, and option lock is more like the way they think – trying to balance all the elements at once, just as in their own lives. But time locks (to women) are just deadlines and seem imposed from the outside rather than open to some degree of control.

Okay, let’s put that behind and see what we can do with this information.

If you want to create a story in which both men and women empathize with the Main Character, then you will want to limit your story with an option lock but employ a Male Mental Sex Main Character. On the other hand, if you want to explore a despicable Main Character, you may not want to disturb your readers/audience by making them empathize with such a cad. In such a case, you can ensure your readers/audience will only sympathize by writing a Female Mental Sex Main Character in a time lock story. The danger is that since nobody empathizes, nobody really gets into the story and it doesn’t sell very well.

Naturally, the other two combinations can also exist – Men Empathize (Male Mental Sex) and women Sympathize (Time Lock) or Women Empathize (Option Lock) and men only sympathize (Female Mental Sex).

You can predict whether a book or movie will attract more men or women, just by seeing who empathizes. Hollywood tends to favor Male Mental Sex / Option Lock stories most often. This has the entire audience empathizing, and therefore (since far more mixed mental sex couples go to movies that single individuals or same mental sex couples) it ensures the largest percentage of the audience is personally involved in the movie, thereby increasing its box office (all artistic merit aside).

Also from Melanie Anne Phillips…

Excerpted from the Book “Dramatica Unplugged“

By Melanie Anne Phillips, Co-creator of Dramatica

Over the years a number of my students have asked how the Dramatica chart can possibly describe the fullness of the human experience, especially since we, as a species, seem to have an unlimited supply of issues?

The quick answer is that even in chemistry there are a limited number of elements yet they combine to create the vast variety of materials in our world. Similarly, we only have a limited number of kinds of issues; they just manifest themselves in different combinations.

But there’s an even better (or at least a more technical) explanation how the vast panorama of our hearts and minds can be captured in a chart of finite size. Bear with me on this, and fasten your mental seat belts….

It is a well-known psychological fact that short-term memory can hold seven items (+ or – 2). We have seven days in a week, seven is considered a magic or lucky number, phone numbers are seven digits (minus the area code).

Why is seven so important? And more important still, what does this have to do with story and the size of the Dramatica Chart? As described above, the Dramatica Chart is built from eight items – the four external dimensions and the four internal ones. And that’s about as big a thought as the mind can hold at one time.

As an illustration, try this thought experiment. Picture a piece of twine. Easy to do. Now, picture that twine twisted along its length like a candy-cane. Again, pretty easy. Next, imagine that twisted twine again twisted into a spiral shape like a slinky. In your mind’s eye, you can probably still see the twists on the twine itself, even while you are also seeing the length of twine wrapped into that spiral shape.

Now, take that slinky-line twine, and spiral the spiral. You know, like you used to do as a kid. You take a slinky, stretch it out, then wrap it around your leg in a spiral. At this point, though it take a bit of work, you can probably still see the candy-cane twists along the body of the twine, even while simultaneously observing the slinky shape of the overall length of the twine and the bigger spiral as it wraps around your leg.

Finally, remove your leg from the center of the largest spirals and assume the twine holds its shape. Try to go one more level and twist the spiraled spiral into a larger spiral, even while maintaining the candy cane twists on the twine itself.

If you are like most people, you’ve reached your limit. You can focus on any part of this construct and see it clearly, as well as the twists one level larger and one level smaller. But to try and picture a three dimensional object that is twisting at four different levels – well that’s seven things to consider and is the limit of short- term memory.

Go any larger and you’d be hard pressed to find someone who could see the smallest twist all the way to the largest at the same time. Theoretically, it is not possible for a mind that exists in a three dimensional brain to go that far.

Why? Well, we have four dimensions in the external world and four dimensions in the inner world. (They really all exist in our minds, but we have four kinds of external measurements we can take to see how things are – Mass, Energy, Space, and Time – and four internal measurements available – Knowledge, Thought, Ability, and Desire.

This gives us eight places to look. But, at any given moment, our mind – the seat of our consciousness – has to be somewhere. So, our “self” sits on one of these areas to look at the other seven. That gives us one place to be and seven slots we can fill with information. And that is why our short-term memory is just seven items.

Getting back to the Dramatica Chart, because it provides all eight dimensions, it can produce with it as much detail as we can hold in our minds at one time without losing track of the big picture.

Recall our discussion of how a story structure needed to include all the ways the audience might consider to solve the story’s problem in order to prove to their satisfaction that the author’s purported solution is the best of the worst. What is to keep the audience from coming up with an infinite number of alternatives? Simply, for any given problem, the capacity of the audience mind is limited by the same seven dimensions (plus one to stand on) factor. If you satisfy all the potential solutions within those eight dimensions, you satisfy the audience because anything larger or small that goes beyond that scope would seem unreasonable or not pertinent.

In Dramatica Theory we call this limit, the Size of Mind Constant. And, we call any story that covers all the reasonable ways in which a given problem might be solved a Grand Argument Story.

Author’s arguments may be insufficient or may be overstated, but a Grand Argument story is one in which the argument is just big enough and no bigger than necessary to cover all reasonable alternatives as defined by the size of mind constant.

And that limit? Well, that’s what determines that the Dramatica Chart is four towers, each with four levels.

So leaving theory behind (for quite a while we hope) all you need to do as an author is explore your story’s problem to full extent of the Dramatica Chart and your argument will be exactly the right size to convince any audience.

Also from Melanie Anne Phillips…

Transcript of the soundtrack from this video:

Class One: Introduction

1.1 Introducing the Story Mind

Let’s look at the central concept in Dramatica: the Story Mind. It’s what makes Dramatica unique. Dramatica says that every complete story is an analogy to a single human mind trying to deal with an inequity.

That’s quite a mouthful, but what it really means is that every complete story is a model of the mind’s problem solving process. In fact, it says that all the elements of the story are actually elements of a single human mind – not the author’s mind, not the audience’s mind but a mind created symbolically in the process of communicating across a medium to reach an audience. It is a mind for the audience to look at, understand and then occupy. That’s the story’s structure itself.

Characters, plot, theme and genre, are not just a bunch of people doing things with value standards in an overall setting. Rather, characters, plot, theme and genre are different families of thought that go on in a Story Mind, in fact that go on in our own minds, made tangible, made incarnate, so that the audience might look into the mechanisms of their own minds – see them from the outside looking in – and thereby get a better understanding of the problem solving process, so when a particular kind of problem comes up in their lives, they’ll have a better idea how to deal with it.

Also from Melanie Anne Phillips…

What is Dramatica?

Dramatica is a theory of story that offers both writers and critics a clear view of what story structure is and how it works. Dramatica is also the inspiration behind the line of story development software products that bear its name.

The central concept of the Dramatica theory is a notion called the “Story Mind.” In a nutshell, this simply means that every story has a mind of its own – its own personality; its own psychology. A story’s personality is developed by an author’s style and subject matter; its psychology is determined by the underlying dramatic structure.

The Story Mind

The Story Mind is at the heart of Dramatica, and everything else about the theory grows out of that. If you don’t buy into it, at least a little, then you’re not going to find much use for the rest of this book. So let’s take look into the Story Mind right off the bat to see if it is worth your while to keep reading…

Simply put, the Story Mind means that we can think of a story as if it were a person. The storytelling style and the subject matter determine the story’s personality, and the underlying dramatic structure determines its psychology.

Now the personality of a story is a touchy-feely thing, while the psychology is a nuts-and-bolts mechanical thing. Let’s consider the personality part first, and then turn our attention to the psychology.

Like anyone you meet, a story has a personality. And what makes up a personality? Well, everything from the subject matter a person talks about to their attitude toward life. Similarly, a story might be about the Old West or Outer Space, and its attitude could be somber, sneaky, lively, hilarious, or any combination of other human qualities.

Is this a useful perspective? Can be. Many writers get so wrapped up in the details of a story that they lose track of the overview. For example, you might spend all kinds of time working out the specifics of each character’s personality yet have your story take a direction that is completely out of character for its personality. But if you step back every once and a while and think of the story as a single person, you can really get a sense of whether or not it is acting in character.

Imagine that you have invited your story to dinner. You have a pleasant conversation with it over the meal. Of course, it is more like a monologue because your story does all the talking – just as it will to your audience or reader.

Your story is a practical joker, or a civil war buff (genre), and it talks about what interests it. It tells you a story about a problem with some endeavor (plot) in which it was engaged. It discusses the moral issues (theme) involved and its point of view on them. It even divulges the conflicting drives (characters) that motivated it while it tried to resolve the difficulties.

You want to ask yourself if it’s story makes sense. If not, you need to work on the logic of your story. Does it feel right, as if the Story Mind is telling you everything, or does it seem like it is holding something back? If so, your story has holes that need filling. And does your story hold your interest for two hours or more while it delivers it’s monologue? If not, it’s going to bore it’s captive audience in the theater, or the reader of its report (your book), and you need to send it back to finishing school for another draft.

Again, authors get so wrapped up in the details that they lose the big picture. But by thinking of your story as a person, you can get a sense of the overall attraction, believability, and humanity of your story before you foist it off on an unsuspecting public.

There’s much more we’ll have to say about the personality of the Story Mind and how to leverage it to your advantage. But, our purpose right now is just to see if this book might be of use to you. So, let’s examine the other side of the Story Mind concept – the story’s psychology as represented in its structure.

The Dramatica theory is primarily concerned with the structure of a story. Everything in that structure represents an aspect of the human mind, almost as if the processes of the mind had been made tangible and projected out externally for the audience to observe.

Do you remember the model kit of the “Visible Man?” It was a 12″ human figure made out of clear plastic so you could see the skeleton and all the organs on the inside. Well that is how the Story Mind works. it takes the processes of the human mind, and turns them into characters, plot, theme, and genre, so we can study them in detail. In this way, an author can provide understanding to an audience of the best way to deal with problems. And, of course, all of this is wrapped up and disguised in the particular subject matter, style, and techniques of the storyteller.

Now this makes it sound as if the real meat of a story, the real people, places, events, and topics, are just window dressing to distract the audience from the serious business of the structure. But that’s not what we’re saying here. In fact, structure and storytelling work side by side, hand in hand, to create an audience/reader experience that transcends the power of either by itself.

Therefore, structure and storytelling are neither completely dependent upon each other, nor are they wholly independent. One structure might be told in a myriad of ways, like West Side Story and Romeo and Juliet. Similarly, any given group of characters dealing with a particular realm of subject matter might be wrapped around any number of different structures, like weekly television series.

But let’s get back to the nature of the structure itself and to the elements that make up the Story Mind. If characters, plot, theme, and genre represent aspects of the human mind made tangible, what are they?

Characters represent the conflicting drives of our own minds. For example, in our own minds, our reason and our emotions are often at war with one another. Sometimes what makes the most sense doesn’t feel right at all. And conversely, what feels so right might not make any sense at all. Then again, there are times when both agree and what makes the most sense also feels right on.

Reason and Emotion then, become two archetypal characters in the Story Mind that illustrate that inner conflict that rages within ourselves. And in the structure of stories, just as in our minds, sometimes these two basic attributes conflict, and other times they concur.

Theme, on the other hand, illustrates our troubled value standards. We are all plagued with uncertainties regarding the right attitude to take, the best qualities to emulate, and whether our principles should remain fixed and constant or should bend in context to particular circumstances.

Plot compares the relative value of the methods we might employ within our minds in our attempt to press on through these conflicting points of view on the way toward a mental consensus.

And genre explores the overall attitude of the Story Mind – the points of view we take as we watch the parade of our own thoughts unfold, and the psychological foundation upon which our personality is built.

You must be logged in to post a comment.